Left Unsaid: Part III – The stigmatization of mental health

December 9, 2013

Part I // Part II // Part III (New Release!)

If you’ve recently felt depressed, alone and overwhelmed, if you’ve felt anxious and hopeless, you’re not alone.

Lives are built and spent on college campuses, and while to a casual observer the fall leaves and sunny days of Cosumnes River College may well seem serene, statistics indicate that many students on campus are struggling with one or many issues that are negatively impacting their mental health and academic performance.

“There are an increasing number of students with serious psychological problems,” said Shannon Dickson, head of the Counselor Education Program at California State University, Sacramento, during the Eighth Annual Fall Ethics Symposium on Mental Health on Oct. 23.

Dickson, a counselor at both CSUS and CRC, shared the panel with the Vice President of Student Services and Enrollment Management, Celia Esposito-Noy.

“What happens outside of campus also happens on campus, meaning, there are students, there are faculty, there are staff and administrators who may indeed have some mental challenges,” Dickson said.

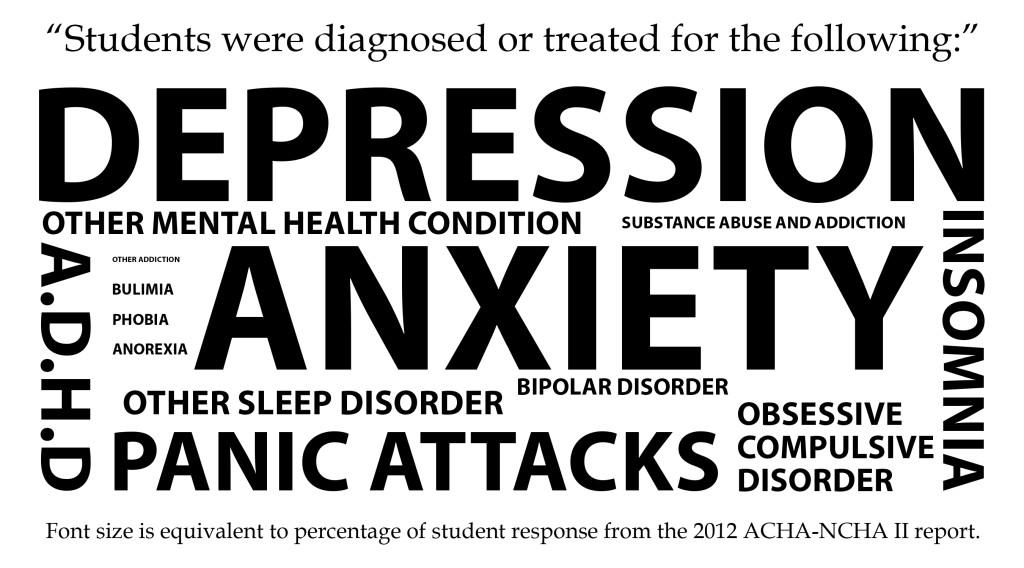

Stress, sleep difficulties, anxiety and depression were only a few in the long list of factors that students reported were negatively influencing their academic performance on campus, according to the Spring 2012 American College Health Association National College Health Assessment II, one of the most recent reports studying the mental health of undergraduate students in the United States.

Of the 76,481 students who responded to the survey, 58 percent said they had felt very lonely, 46 percent said they felt things were hopeless, 43 percent said they had felt “more than average stress” and 7 percent had seriously considered suicide, according to the 2012 ACHA-NCHA II report.

These pressures, along with external factors like limited support systems, personal or family history of substance abuse, chronic stress and peer coping abilities contribute to the overall mental health of a student, Dickson said.

“These risk factors in and of themselves don’t mean anything,” she said. “But when you put these risk factors together, that is when you are going to increase the probability that the student will not matriculate, and it puts the student at a higher risk for developing a mental disorder.”

The ACHA-NCHA report goes on to detail various diagnoses and treatments that students had received within the past year, of which, anxiety (11.6 percent), depression (10.6 percent) and panic attacks (5.5 percent) were the top three.

“Here we have these mental health needs that many colleges feel they are not responsible for,” Esposito-Noy said.

While students at CRC have mental health services through the counseling department, statewide, more than 16 percent of campuses lack services. On average, 26 percent of the funds received from health fees are allocated to mental health services for colleges, according to 2013 Capacity Survey of Mental Health Services Baseline Report from the California Community Colleges Student Mental Health Program.

However, simply because a campus is offering mental health services, it does not mean a student who needs assistance will actively seek them out.

Mental health has a history of being stigmatized and it is these notions, in combination with social pressures and previous school experiences, which keeps certain students from talking to a counselor, Esposito-Noy said.

“It is important to realize that all of us in higher education did not do this alone,” Esposito-Noy said. “Every single one of us has stories of people and resources that have helped along the way. Because, if we hadn’t of been helped, we probably wouldn’t have completed the degrees that we had.”

The need for awareness of students’ mental health at Cosumnes River College was initially raised by long-time advocate and Vice President of Student Services and Enrollment Management Celia Esposito-Noy, who noticed a “sort of heaviness” on campus when she arrived in 2004.

This need, along with rising concerns from administrators and faculty at CRC, resulted in psychology Professor and researcher Jeanne Edman conducting a campus wide study focused on the mental health challenges students were facing.

“She [Edman] asked students to report on some behaviors and feelings over a period of time, which she then measured with the Centers for Disease Control,” said Esposito-Noy. “The scores indicated that students really were indicating levels of depression. It was a significant number, less than half, but still significant enough for us to start paying attention to it.”

These findings were the building blocks upon which mental health services at CRC would eventually be offered.

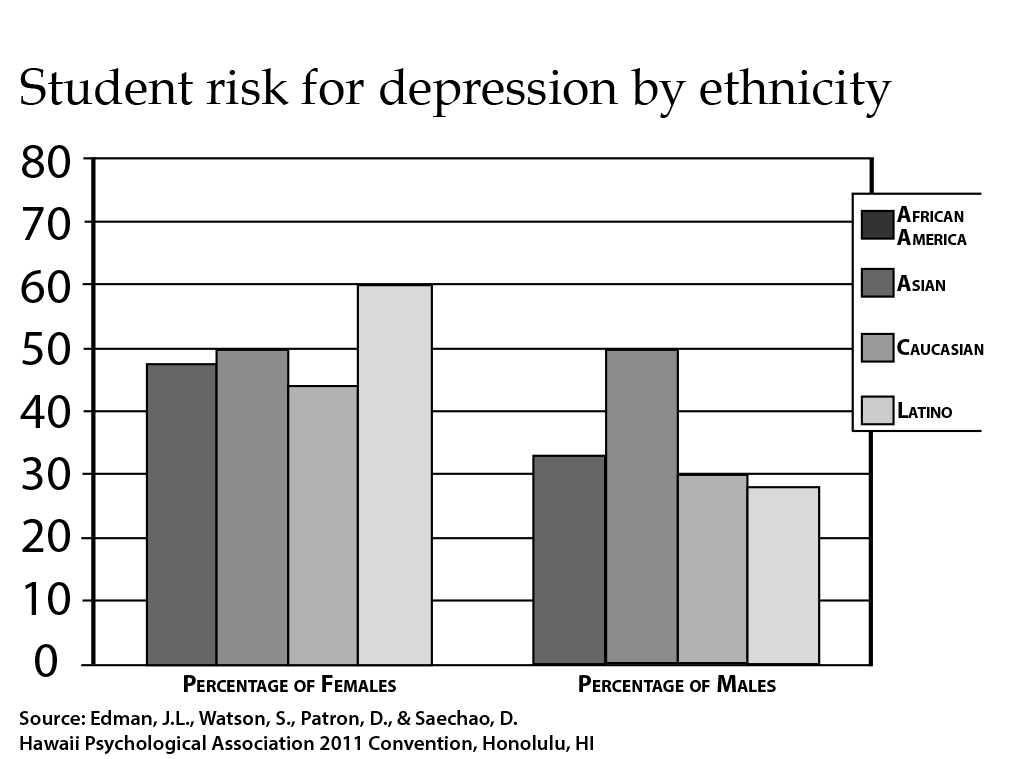

“We found out that females are at a higher risk for depression than males and Asians are at higher risks than other ethnic groups,” said Edman, whose research has continued over the years and into the current term. “About 40 percent of males and 50 percent of females [on campus] are at risk for moderate depression.”

But these percentages beg the question: what is depression?

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, otherwise known as the DSM-5, describes depression in general terms as extended feelings of hopelessness, guilt, dismay and other negative symptoms. However, many would argue that there has not been enough research done to completely understand what causes depression and how it affects the brain and body.

“Anybody that tells you that they know what happens in the brain when you’re depressed is selling you something,” said Psychology Professor James Frazee. “They [drug companies] have never done the research to show that a low level of serotonin is associated with a lower mood. That research is not there. It’s a farce.”

Frazee is in agreement with former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, who argued that the cause of depression truly stems from our busy schedules.

“We are not evolutionarily made to maintain such a stressful lifestyle, which then results in the physiological changes that accompany a diagnosis of depression,” Frazee said. “It’s the best explanation based on the evidence that has been shown thus far. When we look at cultures that have far less than we do, their incidents of depression are far less.”

While the definition and causes of depression may vary and change over time, it was apparent to faculty and administrators that action needed to be taken to counteract the levels of depression recorded for students at CRC in 2008.

“Over the period of about a year or so we assessed and put together a plan, which we have since implemented, that talked about what we need to do in the way of professional development in order to better service students with mental health needs,” Esposito-Noy said.

These needs are apparent to many professors who interact with students on a day-to-day basis.

“I see it in my students that there is a profound need [for mental health services],” Frazee said. “And what ends up happening is a lot of the times people get social workers or psychiatrists who will shuffle them in and medicate them instead of spending the time to do the work to rebuild a person who has been broken.”

One year after Edman’s initial report, the group Multicultural Counseling Consultants and Associates won the Los Rios Community College District contract for training on crisis intervention, and as a result Dr. Shannon Dickson, head of the Counselor Education program at California State University, Sacramento, began her work on the mental health services offered at CRC.

“Having the services on campus is consistent with having students succeed academically,” said Dickson, who, along with an intern, provides 40 hours a week of one-on-one counseling for students through the counseling department.

“Students are referred to us through academic counselors, nursing staff, and also administration,” she said. “My schedule is often full and I know that my intern’s schedule is full, so we’re not able to see the number of students that might desire or are referred to us for counseling.”

However, the balance between availability and need of mental health services is closely monitored and regulated by the state, limiting the help that can be provided.

“Students may get anywhere from one to three sessions,” Esposito-Noy said. “They may talk about coping strategies, reducing stress and managing family, school and life issues. From there, if it’s determined that they need long term counseling they will be referred out to a local agency.”

While students are responsible for following up on referrals to an outside agency, a first step to recovering and coping with depression or any form of mental illness is reaching out and talking about it.

“Somebody has been where you are and you are not alone,” Frazee said. “Somebody actually cares about you as a person and it is not hopeless, despite how it feels. You are in the matrix of depression and the world that you see is not real. You can come back to this one anytime, you just need help.”

People have struggled with mental health throughout the course of human history and accompanying that battle is a social stigmatization of both the conditions and those who are affected by them. While this silence is gradually breaking, it has long been an issue left ignored and unsaid.

Historical figures such as President Abraham Lincoln, the scientist Isaac Newton, the poet Sylvia Plath, the author Ernest Hemingway and the mathematician John Nash have all been retrospectively diagnosed with one form of mental illness or another, according to the website for Rutgers graduate school of applied and professional psychology. Yet, little mention of their conditions can be found in a standard historical textbook.

“Mental health is a prime example of something that our society stigmatizes, we attach a negative evaluation to it,” said Cosumnes River College Philosophy Professor Richard Schubert. “We think that people with mental illness are best avoided and we believe that we will be avoided if other people understand we have a mental illness.”

However, at CRC it may be difficult to avoid students struggling with mental health challenges. Approximately half of all students on campus are at risk for moderate depression, according to an ongoing study conducted by Psychology Professor Jeanne Edman.

“I see many students fail who occupy a seat in the course without completing it in a satisfactory manner,” Schubert said. “Not because they are not intelligent enough or motivated enough, but because they have mental health challenges.”

This correlation between mental health and student success has long been championed by Vice President of Student Services and Enrollment Celia Esposito-Noy who began the process of offering mental health services to students on campus in 2004.

These services, while limited due to the number of counselors available on campus, are known by many students.

“I have used our mental health counseling to help better myself to go into pharmacy,” said Brandon Deniz, a 17-year-old pharmacy technology major. “I don’t think having a mental health issue or using mental health services is something to be embarrassed about.”

Others, unaware of the help offered on campus, expressed a different perspective on seeking and using mental health services.

“I wasn’t aware of it, but I would use it if I needed it,” said Neal Luu, a 21-year-old business major. “It’s something to be embarrassed about to a certain degree but it shouldn’t stop you from getting help.”

Stigmatization aside, the fact remains that many students are directed through the proper channels and utilize these services that have been offered for several years.

“I think that the campus is deeply indebted to Vice President Esposito-Noy for finding a way, despite the budgetary difficulties and legal liability challenges, to offer some mental health services,” Schubert said.

The services offered at CRC, such as counseling and references to outside organizations, were orchestrated by Shannon Dickson, head of the counselor education program at California State University, Sacramento, who has noticed a gradual acceptance of mental health issues on campus.

“When I started a few years ago, students were a lot more reticent because of the media and the different stories of people with mental health problems,” said Dickson. “But subsequently since being here over the past four years, I think that the faculty, classrooms and even administration have spoken very highly and positively about our services, so students are more engaged in the process and more willing to come to counseling.”

This change is slow for many reasons, foremost the inherent and underlying exclusion of those with mental health challenges.

“There are a lot of different reasons why students are apprehensive, as are faculty and staff, about self-identifying or about asking for help,” said Esposito-Noy. “Because, unfortunately, it’s easier for people to say ‘I have high blood pressure’ instead of ‘I have a mental illness.’”

Admitting and self-identifying the need for mental health assistance may be uncomfortable for students but it is considered crucial among the administration and faculty of CRC, many of whom recognize the influence and stigma that society has placed on our view of mental illness.

“It’s absurd to think that people’s disabilities, whether physical or mental, are a result of some failing on their part,” Schubert said. “We don’t pick our genes and we don’t pick our environment.”

However, it is suggested that the presence of a stigma should not keep students from seeking support or mental health services, whether it is through the school, family or an outside organization.

“If you have a mental illness and you know that something is good for it, and you choose not to do it, the illness is on you,” said Psychology Professor James Frazee. “That stigma, although it is there and real, shouldn’t preclude anybody from seeking treatment because it is that important.”

It is recognized that as a society we have gradually decreased the stigmatization of mental health and become more accepting of those with mental illness or challenges, but in no way should the work be considered done.

“Are we still prejudice against people with physical and mental disabilities? Yes. Have we made progress? Yes,” Schubert said. “Is there a lot more progress that needs making? Absolutely.”

(Amari Gaffney contributed to Part III of this article)